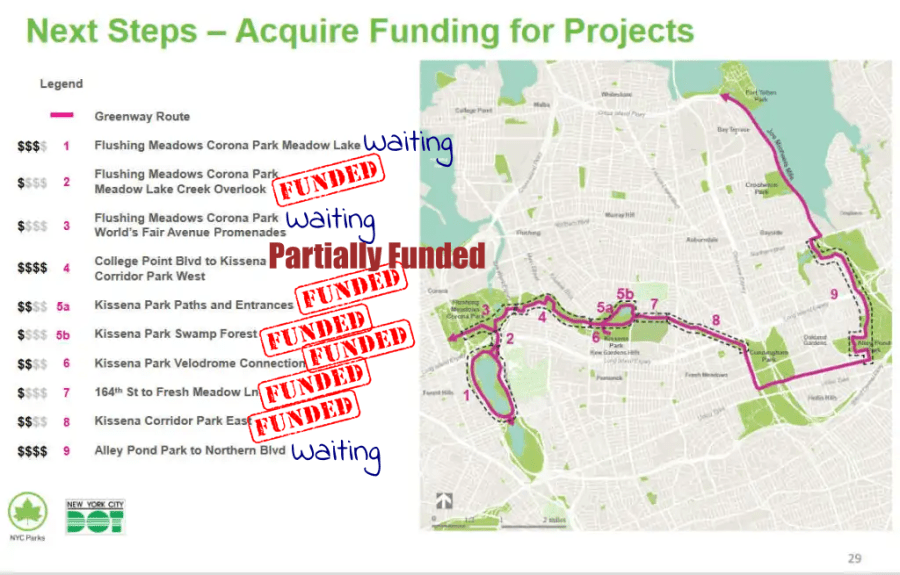

More than six decades ago, New York City envisioned a transformative project—an uninterrupted protected greenway connecting Fort Totten at the northeast tip of Queens, to Coney Island on the southwest tip of Brooklyn. Today, our portion of the Eastern Queens Greenway is mainly funded but remains stalled, while much of the Brooklyn section is not even in conversation. Despite community support, multiple rounds of planning, and over $43 million allocated to various components, the ground remains untouched for years, and neighborhoods continue to suffer.

Delays That Define a Generation

The Eastern Queens Greenway advocacy group has spent 15 years pushing for a Greenway vision first laid out in the 1960s. But the timeline keeps slipping, like these recent delays:

- The Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Destination Greenways Meadow Lake Segment is now tangled with State DoT’s Van Wyck Expressway construction, pushing back procurement out to February 2026, adding an extra year to the project timeline.

- The Joe Michaels Mile Waterfront Structural Reconstruction, delayed by coordination with FEMA-funded work, is now pushed back to October 2025—eight months behind their last schedule.

- The Kissena Corridor and Kissena Park segments, now intertwined with the city’s newly announced Cloudburst Resilience initiative, face additional slowdowns despite overwhelming local support for both flood protection and Greenway infrastructure.

While the Cloudburst plan aims to bolster resilience, residents worry it’s sidelining vital Greenway access, stalling a project already in motion. While we understand the City is trying to address two issues with one project, it’s time for them to present one timeline and some visuals to the community that has devoted so much effort working with officials to allocate the funding. Is our project being “watered down” so the money can serve other goals?

That concern deepens with spending priorities—like the $7 million earmarked for Kissena Park bathrooms coming out of the $43 million dedicated for the full Eastern Queeens Greenway path. Our team supports amenities but has always urged these upgrades come last—not before safety-critical routes.

Worse, delays amplify costs. Inflation chips away at budgets, forcing scaled-back designs that compromise the true safety projects. Deferred timelines mean fewer protected segments and smaller plans, undercutting the very benefits the Greenway was meant to deliver. What starts as visionary slowly gets reduced to vulnerable.

The Hard Cost of Delay: Real People Getting Hurt

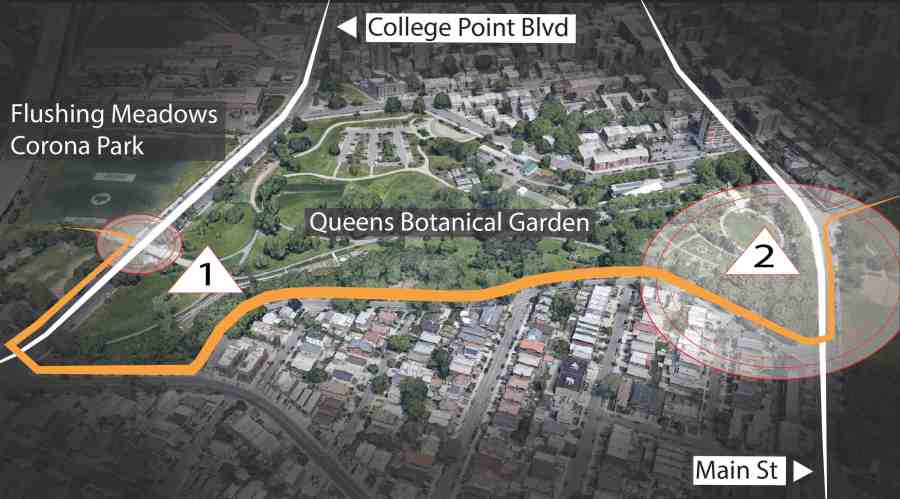

The yet-to-be-built Greenway section around Queens Botanical Garden and over the College Point Boulevard Bridge, acknowledged as the most dangerous segment for pedestrians and cyclists, still lacks even a basic design for construction.

The delays on the east/west path through Kissena Corridor Park means residents are forced onto Colden Street, a variable width street that encourages drivers to ignore the stop signs. When IS 237 (the Rachel Carson School) closes Colden for student safety, cyclists are pushed to Kissena Boulevard, a deathtrap that the class 3 bike lane (sharrows) does nothing to protect. If the Greenway plan was not delayed, cyclists and pedestrians would have a safe, enjoyable path through the park, instead of fighting for their lives on these streets.

Proof That Parks Work

Evidence of success is everywhere—when it’s actually built. The Meditation Garden in Kissena Corridor Park, championed by the Kissena Corridor Park Conservancy, now offers a restorative space for patients at Booth Memorial Hospital, in addition to the entire community. It also stopped the illegal dumping rampant in that area and has stopped the City from renting out the parkland for parking spots, like it used to do there.

Cunningham Park, previously marred by ATV abuse and illicit drug gatherings, now has volunteer-built mountain bike trails that have changed everything. Cyclists became stewards, pushing out the crime. Forestland transformed from vulnerable to vigilantly protected.

The formula is simple: activate public space, and people look out for each other.

Councilmember Sandra Ung, the key force behind the Greenway funding drive, has seen the fallout firsthand. Fewer park visitors leaves space for serious crimes in our parks. The construction delay doesn’t just obstruct pedestrians and cyclists—it erodes safety, peace, and civic trust. Councilmember Ung’s push to improve parkland access is the only way the Greenway has made any progress.

Getting Out Of A System Stuck in Neutral

This is about more than pavement and paths. When a government cannot complete straightforward projects, residents lose faith. The Greenway is precisely the kind of initiative that should unify environmental goals, mobility, recreation, and safety (all without any of the backlash bike-lane projects receive). We, more than anyone, respect studies on the project’s impact to animal’s habitats, storm water runoff, how this connects to the street network…but at the end of the day, paving a concrete path through New York City parkland shouldn’t be measured in decades. It’s caught in a system that demands generations of advocacy for inches of progress—unless you’re wealthy.

The contrast is stark. As the Greenway languishes, billionaire Steve Cohen swiftly advanced plans to privatize parts of Flushing Meadows Corona Park for his personal casino—despite intense community opposition. The lesson? Speed and success depend not on merit or community value, but money and corruption. The system is designed to work really well, but only for people that have so much wealth that they’d never live here.

A Call to Rebuild Trust and Progress

Most city employees and agency representatives we work with are dedicated professionals doing their best within a broken framework. But right now we’re all responsible for changing that framework. At every level—from federal to city—voters have clearly demanded a change because the old government isn’t working for the people anymore.

The Greenway is not just a path—it’s a promise. A promise that our government can listen, respond, and easily build something good for its people. That safe green space isn’t a luxury, but a right. Local voices, not just moneyed ones, deserve attention.

In a city defined by its pace, let’s stop measuring community dreams in decades. Our neighborhoods aren’t asking for miracles. We’re asking for momentum.

[…] have heard of Eastern Queens Greenway delays due to inter-agency friction, including the State DoT’s Van Wyck Expressway construction, […]

LikeLike

[…] (for at least some sections) and have $43.4 million dollars dedicated to it, we are still seeing delay after delay from the Department of Parks. If the greenway was finished by now, not only would this ride be […]

LikeLike

[…] Corona Park isn’t over—and your voice is needed now more than ever. You’ve seen the many articles we wrote about this parkland theft Steve Cohen is stealing from you, with the help of a […]

LikeLike

[…] Peck Park’s promised section of the Eastern Queens Greenway has lingered in the Parks Department’s pipeline for years. Local advocates have pressed for a design plan and construction timeline, but all they’ve received are vague assurances and shifting deadlines. Without a protected greenway path through this critical park, cyclists are funneled back onto Hollis Court Boulevard—directly into harm’s way. […]

LikeLike